How Housing First stabilizes mental health

Without stable housing, meaningful mental health treatment is nearly impossible.

Responses to homelessness often treat mental health care as a prerequisite — expecting individuals to stabilize symptoms, address substance use, and demonstrate compliance before accessing housing. Providers working on the ground across Michigan say the reality is often the opposite. Without stable housing, meaningful mental health treatment is nearly impossible.

That belief sits at the core of the Housing First model, an approach that prioritizes permanent, stable housing as the starting point for recovery rather than a reward for progress. Across Michigan in counties like Allegan and Sanilac, Michigan’s behavioral health leaders say Housing First is not only humane, but practical, creating the conditions necessary for people to engage in care, reduce crisis cycles, and regain stability.

According to Michigan’s 2023 Ending Homelessness in Michigan Annual Report, substantial numbers of people experiencing homelessness report behavioral health challenges — with statewide data showing mental health and substance use disorders figures in the 20–30% range among subpopulations counted in the Homeless Management Information System. Rural counties face additional barriers, including limited housing stock and fewer behavioral health providers, making Housing First approaches especially critical outside urban areas.

Housing as the foundation, not the finish line

National studies consistently show that Housing First programs increase housing retention rates to 85–90% after one year, even among people with serious mental illness or substance use disorders. Research published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has found that people placed into permanent supportive housing experience fewer psychiatric hospitalizations, reduced emergency room use, and improved engagement in outpatient mental health care.

At OnPoint, Allegan county’s community mental health agency and housing authority, Housing First is built on structure rather than discretion. Mark Witte, OnPoint CEO, explains that the model relies on standardized assessments developed at the federal and national level to determine priority.

“If somebody calls, emails, or walks in to access housing, we follow a structure,” Witte says. “We identify how long they’ve been homeless, whether there are children involved, whether domestic violence is present, whether they’re a veteran, etc. We don’t look at somebody and say they’re more or less worthy. We follow the system that’s been put into place.”

That system addresses the most urgent needs first, while removing the moral lens that has historically shaped housing access. For Witte, the misconception that Housing First “doesn’t work” ignores both the evidence and the lived realities of homelessness.

“It’s disheartening,” he says. “The entire point is that stabilization enables access, not the other way around.”

Why mental health can’t come first without housing

Heidi Denton, a prevention specialist on OnPoint’s housing team, grounds that logic in a familiar framework, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which holds that people cannot meaningfully address mental health, trauma, or recovery until their most basic needs like food, safety, and shelter are met.

“You really can’t pay attention to higher-order concerns like relationships, trauma, or mental illness until basic needs are met,” Denton says. “Food, clothing, shelter, safety, those come first. Housing isn’t a reward for becoming stable. It’s a building block for stability.”

Denton describes how homelessness disrupts even the most basic logistics of care. Without a consistent place to sleep, charge a phone, shower, or make coffee, keeping appointments becomes unrealistic. Outreach workers may schedule a meeting, only to lose contact when someone’s phone is shut off or they’re forced to move from one temporary location to another.

“If we can get them housing first, we know where they are,” Denton said. “They have a warm bed, a shower, a place to make coffee. That sounds basic, but it’s everything.”

Stabilization alone can reduce substance use

Denton points to a Housing First site visit in Minnesota that challenges common assumptions, an example of how low-demand housing, which does not require sobriety as a condition of placement, is used to engage people with significant substance use disorders.

Rather than mandating treatment or abstinence upfront, Denton explains, the model centers stability as the starting point. In her experience observing low-demand housing, simply placing people into housing changes how they engage with services.

The approach runs counter to long-held assumptions that sobriety or treatment readiness must precede housing. Instead, Housing First reframes stability itself as a form of harm reduction, creating the conditions under which people are better able to address substance use, mental health needs, and recovery over time.

Multiple evaluations of Housing First programs show reductions of about 50% in emergency room visits and inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, along with significant declines in jail bookings. A landmark analysis found that the cost savings from reduced crisis services often offset or fully cover the cost of providing permanent supportive housing.

Witte cautions against oversimplifying the relationship between homelessness and mental illness. While they frequently coexist, he says, homelessness itself often exacerbates symptoms and complicates recovery.

“I’m not sure that people who are homeless struggle with different kinds of mental illnesses than others,” Witte says. “But homelessness and mental illness are often found together.”

Some individuals, particularly those experiencing schizophrenia or severe paranoia, may initially resist housing altogether. Others make strategic decisions based on fear of losing limited assistance, such as delaying moving into housing until winter to ensure shelter during the coldest months.

“People are doing what they can with the tools they have to manage their lives,” Witte says.

The role of community partnerships

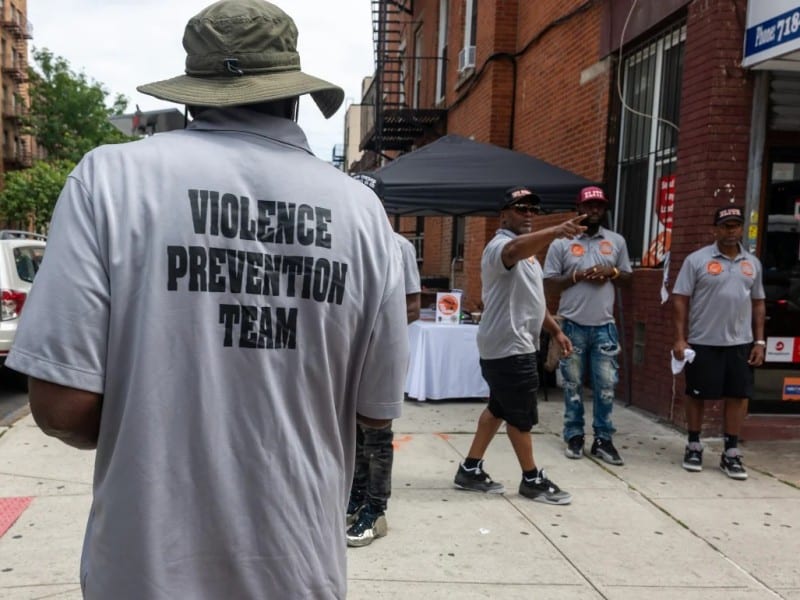

Once housing is secured, community partnerships become critical. OnPoint works closely with food pantries, donation centers, and local organizations to ensure newly housed residents have the basics needed to live safely — beds, cookware, clothing, and food.

“We can call a pantry and say, ‘This family is in crisis,’” Denton says. “They’ll have three days of food ready for us.”

But Witte emphasizes that housing alone does not erase years of instability.

“There’s an assumption that once someone is housed, they should just know how to be a tenant,” he says. “But nobody taught them. Case management doesn’t stop at the lease.”

A perspective from Sanilac County

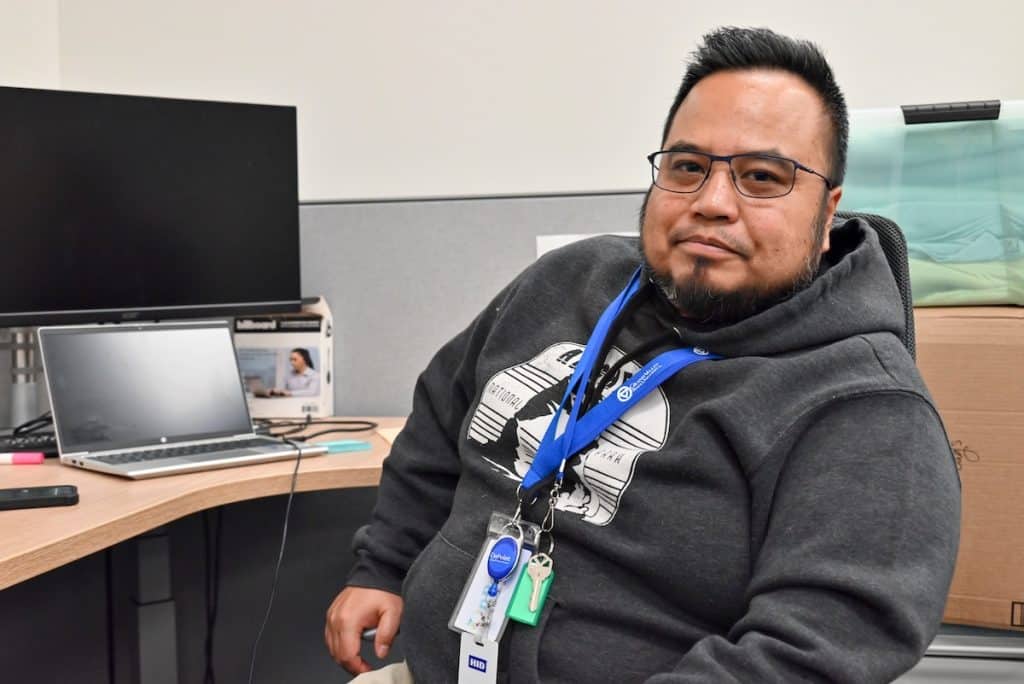

In Sanilac County, where housing resources are even more limited, Nicole Beagle, chief operating officer at Sanilac County Community Mental Health (CMH), sees the same dynamics play out, often with fewer tools.

“When basic needs like housing aren’t met, it becomes overwhelming,” Beagle says. “People can’t focus on mental health or recovery when they’re worried about food, water, or where they’re sleeping.”

Sanilac County CMH collaborates with a men’s shelter, a domestic violence shelter, and regional housing assistance programs while also providing on-site case management and peer support.

“Once housing is secured, people are far more likely to engage in services,” Beagle says. “They’re more focused on becoming stable because their basic needs are met.”

Structural barriers beyond housing

Even with housing assistance, barriers such as transportation, employment, and criminal records continue to shape outcomes, particularly in rural areas.

“Transportation alone can derail everything,” Beagle says. “You might have to get on a bus at 7 a.m. to make a noon shift, and then miss mental health appointments because of it.”

Studies show that people experiencing homelessness are up to three times more likely to miss medical and mental health appointments than housed individuals. Once housing is secured, appointment adherence and continuity of care improve significantly. This is a pattern providers attribute to stability, reliable contact, and reduced daily survival stress.

Criminal background checks further restrict housing access, even for individuals actively engaged in treatment. These structural barriers, she said, are often outside the control of local agencies.

“We have to be creative with the resources we do have,” Beagle says. “The gaps aren’t always something we can fix locally.”

Funding threats and the future of Housing First

While Housing First models have expanded over the past two decades, Witte warns that proposed federal funding shifts could undermine their effectiveness. Much of Allegan County’s housing work is funded through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which has signaled interest in reducing permanent housing support in favor of short-term assistance.

“That would be a very significant threat to the stability we’re trying to build,” Witte says. “Decisions made in Washington have direct impacts on rural counties like ours.”

For providers, the connection between housing policy and mental health outcomes is clear.

“If people understand anything from this,” Witte says, “it should be that housing policy and mental health success are tightly connected.”

Photos by John Grap.

Photo of Nicole Beagle courtesy Sanilac County Community Mental Health

The MI Mental Health series highlights the opportunities that Michigan’s children, teens and adults of all ages have to find the mental health help they need, when and where they need it. It is made possible with funding from the Community Mental Health Association of Michigan, Center for Health and Research Transformation, OnPoint, Sanilac County CMH, St. Clair County CMH, Summit Pointe, and Washtenaw County CMH and Public Safety Preservation Millage.