Children’s mental health: When and where to access care

Local CMHs, CCBHCs, and primary care providers can serve as critical starting points, connecting children to mental health care.

Across Michigan, children and adolescents face rising mental health challenges, from anxiety and depression to behavioral crises that disrupt school and family life. At the same time, families seeking help often encounter long wait times, workforce shortages, and confusion about where to start, especially when needs escalate quickly.

Local community mental health agencies and statewide health policy experts say demand for children’s services has grown steadily in recent years, fueled by social pressures, increased awareness of mental health needs, and a system strained by limited staffing and inpatient capacity.

At both St. Clair County Community Mental Health (CMH) and LifeWays Community Mental Health in Jackson County, clinicians report that children are being referred for services at younger ages and for more complex concerns.

“We’re seeing a lot of anxiety, depression, and difficulty with emotional regulation,” says Kathleen Gallagher, chief clinical officer at St. Clair County CMH. “There’s a lot of uncertainty in the world, and kids pick up on that. Social media and online bullying have really changed the landscape. It’s no longer something kids escape when they go home.”

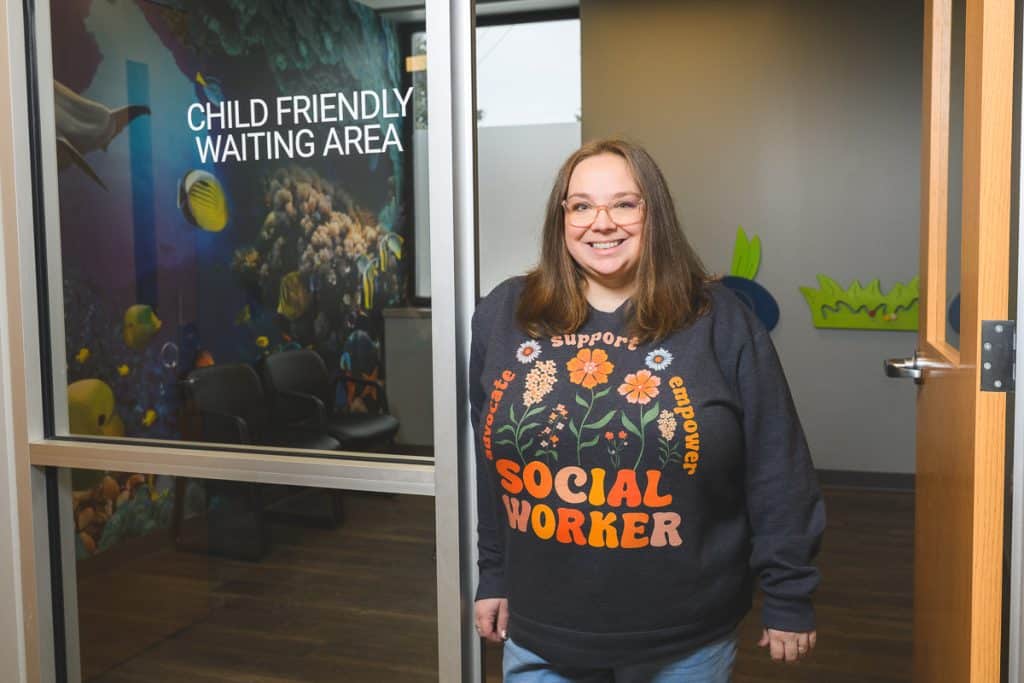

“We’re supporting children who’ve experienced trauma at school, in their homes, or in their communities,” says Jessica Hendricks, outpatient supervisor at LifeWays. “Schools are often a major referral source, especially when behavioral challenges are impacting a child’s ability to be successful during the school day.”

Rising needs, earlier ages

Hendricks says referrals often involve hyperactivity, emotional dysregulation, aggression, or difficulty maintaining friendships — issues that can signal deeper mental health needs when left unaddressed.

To respond, LifeWays offers a continuum of children’s services spanning infancy through adolescence. That includes infant mental health home-visiting programs focused on attachment and early development, outpatient therapy for school-aged children, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents, and parent-focused interventions to help caregivers manage challenging behaviors.

Similar to Lifeways, St. Clair County CMH offers a wide range of services designed to support children and families at different stages and levels of need. Those offerings span outpatient therapy, intensive home-based services, infant and early childhood mental health programs, crisis response, case management, and family-centered supports. These allow clinicians to tailor care based on a child’s age, symptoms, and family circumstances. Leaders say this continuum is essential, as children’s mental health needs rarely fit into a one-size-fits-all model and often shift over time as stressors, environments, and developmental stages change

“When a child has significant behavioral or mental health challenges, it can be incredibly hard on parents,” says Debra Johnson, CEO of St. Clair County CMH. “Sometimes caregivers need support too, to learn strategies and take care of themselves.”

What happens when families reach out?

For families unsure of where to begin, both agencies emphasize that the first step is often simpler than parents expect.

At St. Clair County CMH, parents can call a central intake and access line, where staff conduct an initial screening and connect families to appropriate services or referrals. Gallagher described it as “a pretty easy process,” noting that families can also be referred elsewhere if the CMH is not the best fit.

LifeWays uses a similar access model, beginning with a screening and intake assessment through its access center. From there, children may be connected to therapy, psychiatry, case management, crisis services, or partner providers within LifeWays’ broader network.

Hendricks says that the approach is designed to reduce overwhelm.

“We want families to know we’re glad you’re here,” she says. “You are the expert on your child. We’re here to partner with you.”

Barriers remain, especially for crisis care

Despite strong local programs, significant gaps remain statewide, particularly for children needing higher levels of care. Michigan faces a persistent shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. According to data cited by the Center for Health Research & Transformation (CHRT), the state has more than 2 million children but only about 280 child and adolescent psychiatrists, with many counties having none at all.

“That workforce shortage leads to not enough psychiatric beds and too many kids presenting in emergency departments during a crisis,” says Nancy Baum, health policy director at CHRT. “They’re not getting care early when it could prevent things from escalating.”

Johnson echoed that concern, pointing to a severe lack of inpatient psychiatric beds for children statewide and limited residential treatment options.

“There are times when kids who need the highest level of care simply don’t have a place to go,” she says.

Staffing shortages further complicate access. Like many of Michigan’s CMHs, both St. Clair County CMH and LifeWays report difficulty recruiting and retaining master’s-level clinicians, particularly for public-sector behavioral health work.

That workforce shortage has cascading effects, contributing to a lack of staffed inpatient psychiatric beds and leaving many children in crisis waiting for care in emergency departments that are not designed to meet pediatric mental health needs.

Baum points to upcoming infrastructure changes that could help ease some of that pressure. A new state psychiatric hospital for children and adolescents is expected to open in Northville at the former Hawthorne Center site, adding roughly 70 inpatient beds for youth statewide. This facility could help address one of the most acute gaps in the system: access to appropriate inpatient care for children experiencing severe mental health crises.

Even with expanded inpatient capacity, Baum emphasizes that most children’s mental health needs are best addressed long before hospitalization is necessary through early intervention, community-based services, and primary care.

Promising models and statewide efforts

Even amid these challenges, providers and policy experts point to models that are expanding access and showing results. Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs), which serve individuals regardless of insurance status, are one such model. CHRT recently analyzed survey data from Michigan CCBHCs and found improved access, high family satisfaction, and positive outcomes for children and youth receiving services.

Other initiatives, such as the MC3 and Zero to Thrive programs, connect pediatricians and primary care providers with child psychiatrists through consultation and telehealth, bringing expertise to areas of the state lacking specialists.

Baum emphasizes that primary care remains an often-overlooked entry point.

“About half of mental health services are actually provided in primary care,” she says. “For families who can’t find specialty care right away, a pediatrician is a really important first step.”

Knowing when to seek help

Clinicians agree that parents don’t need to wait for a crisis to ask for support. Changes in sleep, eating, mood, academic performance, or social behavior can all be warning signs, especially when they represent a shift from a child’s usual baseline. Younger children may express distress through physical complaints like stomachaches or headaches, rather than words.

“If something feels different or concerning, call,” Gallagher says. “You don’t have to be in crisis to reach out.”

Johnson adds that reducing stigma remains essential.

“Asking for help is a good thing,” she says. “Mental health care is something any of us could need at any time.”

For families navigating a complex system, local CMHs, CCBHCs, and primary care providers can serve as critical starting points — connecting children to care that may help stabilize not only their mental health, but their long-term well-being.

Photos by Doug Coombe.

Photos of Jessica Hendricks and Deb Johnson courtesy subjects.

The MI Mental Health series highlights the opportunities that Michigan’s children, teens and adults of all ages have to find the mental health help they need, when and where they need it. It is made possible with funding from the Community Mental Health Association of Michigan, Center for Health and Research Transformation, OnPoint, Sanilac County CMH, St. Clair County CMH, Summit Pointe, and Washtenaw County CMH and Public Safety Preservation Millage.